It was a Tuesday night in London when Richard James Burgess found himself on the doorstep of Blitz for the very first time. He was dressed in ripped jeans and a t-shirt, surrounded by people with “amazing clothes and amazing hair.”

Unbeknownst to Burgess at the time, that door was, in reality, a gateway that would ultimately lead him to coin the term “electronic dance music” in 1980. It landed him at the forefront of a sonic revolution—one marked by experimentation and a desire to “electrify” the acoustic instruments of the heyday.

And it all started out with a drum set and a dream.

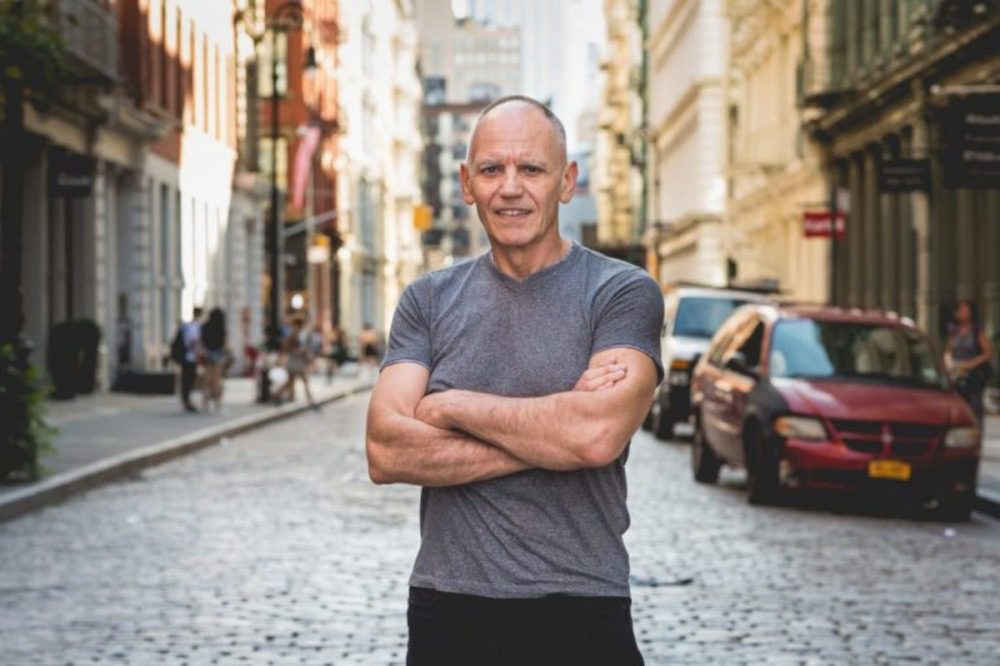

Richard James Burgess is now the President and CEO of The American Association of Independent Music.

Born in London and raised in New Zealand, Burgess was drawn to percussion at an early age, for one reason or another: “I picked the drums because I thought, ‘Well, I can do that,’” Burgess jokingly told EDM.com at a coffeehouse in Beverly Hills.

By the time he was 15, Burgess was making enough money as a musician to pursue a full-time career. It was a journey that would crisscross the globe, contributing to a countless number of records for iconic labels like RCA and Capitol.

But one of the things that set Burgess apart—and ahead—was his love for synthesizers. This began with the EMS Synthi A, an analog synthesizer and matrix pad built into a suitcase.

“My first question was, ‘How do I make drum sounds on this thing?’ I was really becoming obsessed with the idea of electronic drums,” Burgess recalled.

He later got his hands on devices like the ARP 2600, the Roland MC8 and, his own co-invention, the prototype of what would become the SDS-5 (“literally a piece of wood with wires and components on it”).

“People would say, ‘Oh, but that doesn’t sound real.’ And I’d go, ‘No! But it sounds cool!’” he said.

Records by Tonto’s Expanding Head Band, Stevie Wonder and Wendy Carlos showed Burgess, a self-described “sponge,” what was possible. And then, a Monday night rehearsal band became the platform for those ideas to become reality.

Formed in London in the mid-70s with Christopher Heaton, Andy Pask, Peter Thoms and John L. Walters, Landscape was known for its early, synthwave-era embrace of computer programming. At one point, Burgess even pulled the microphones out of telephone handsets and wired them into his drum kit so they could trigger different synthesizers with every hit.

Walters played the lyricon, the world’s first electronic wind controller, while Heaton, Pask and Thoms developed and mastered synthesizers that manipulated their own acoustic instruments.

Landscape’s music was vivacious. It coupled playful melodies with the feel of the future, rounded out by big ensemble vocals and quirky sonic textures: “Avant garde electronic stuff, 100% improvised,” Burgess affirmed.

One of their tracks, “Einstein a Go-Go,” was the first computer-driven song to become a top five hit in the U.K.

Recommended Articles

Inside the Origins of "EDM" With the Man Who Coined the Term—And Transformed It Into a Global Movement

An intimate interview with Richard James Burgess, whose band, Landscape, coined the term "EDM" in 1980—and had no clue what would happen next.

Steve Aoki and TOKiMONSTA to Perform At FVCKRENDER's NFT.NYC Experience

Presented by leading digital artist FVCKRENDER, the "LVCIDIA Experience" is coming to New York for a multi-faceted, three-day NFT experience.

An Insider’s Guide to Sacred Acre Festival 2022

With Sacred Acre approaching, we compiled everything you need to know for a memorable festival experience.

Together, they decided early on that “it was better to be part of a movement than just be a single band,” Burgess said. And it was within the four sweaty walls of the Blitz club where the band found its company.

Popularized by influential Visage frontmen Rusty Egan and Steve Strange (“Fade To Grey,” “Mind of a Toy”), Blitz was all things “weird and wonderful,” even engendering a cohort of so-called “Blitz Kids” who went on to become fashion designers, neo-glam tastemakers and cultural commentators. Strange functioned as the venue’s host and promoter (“the look,” Burgess coined), and Egan its sonic architect.

“I walked in and it just blew my mind,” Burgess remembered of his first Tuesday night at Blitz. “David Bowie, Roxy Music, Kraftwerk, Yellow Magic Orchestra, Fad Gadget—[Egan] was finding all the records out there that were somewhat electronic, including Landscape’s…and figuring out what fit within the scene he was trying to create there.”

We were like, "How about EDM?"

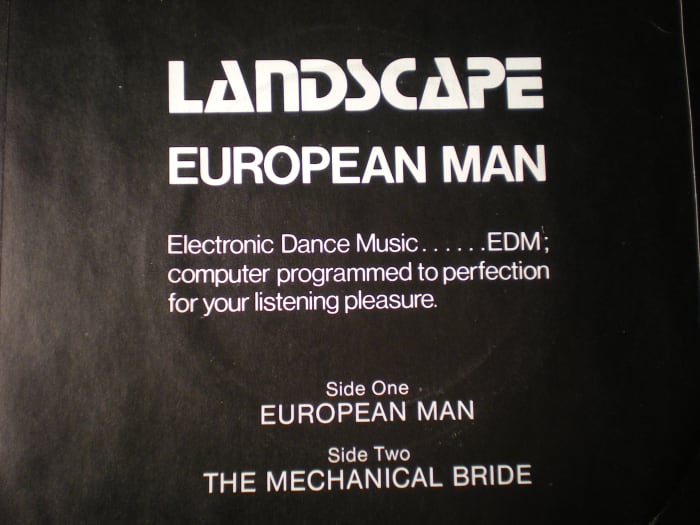

In 1980, a particularly funky Landscape record titled “European Man” made it official. “EDM; computer programmed to perfection for your listening pleasure,” its cover read.

“We knew it was electronic. We knew it was dance,” Burgess explained. “Out of that came ‘electronic dance music,’ but we thought that was kind of long. We were like, ‘How about EDM?’”

“I wasn’t thinking, we’ll name a genre here, we’ll name a movement,” he added. “It’s just something you say.”

“I wasn’t thinking, we’ll name a genre here, we’ll name a movement,” Richard James Burgess told EDM.com.

c/o Richard James Burgess

Fast-forward four decades, and Landscape’s humble acronym has exploded from an unpretentious slogan into a multi-billion dollar empire. Burgess was even appointed Member of the Order of the British Empire in 2022 for his services to music.

Yet while the superstars, scale and scope of EDM may have changed, what hasn’t, Burgess strongly believes, is its spirit.

“This was just a bunch of freaks together enjoying something that was unique to us. It was wild and exciting,” Burgess reflects. “I think people are always seeking out those immersive experiences, and with the EDM experience, it’s full body and full mind.”

Coincidentally (if you believe in those sorts of things), Burgess and modern-day EDM moguls are still on the same page when it comes to elevating the experience: the metaverse. The likes of Eric Prydz, Black Coffee, Carl Cox, David Guetta and Charlotte de Witte are already DJing exclusive sets in the Sensorium Galaxy, and in March, Insomniac announced a partnership that would develop the next generation of live music experiences in the metaverse.

“There’s a huge amount of potential. Like when Walkmans came out, you’d see people on the train sharing a wired earbud. I’ve got to imagine that we’ll move toward a more shared VR experience,” Burgess said. “I believe, in a way, the Blitz was a metaverse. It was a real metaverse, but it was a metaverse.”

But it’s not just the tangible listening experience wherein Burgess sees a future. As the President and CEO of the American Association of Independent Music (A2IM), he views digital development as a promising catalyst for industry equity across the board, from gender and race to artists’ rights and community growth.

One playing field that has already been leveled is music ownership. 3LAU’s NFT marketplace, Royal, for example, facilitates the direct sale of royalties to fans who invest in tokenized music. The company’s most recent funding round nabbed $55 million from The Chainsmokers, Logic and Kygo, among other high-profile investors.

“The thing about human beings that’s exciting to me is how adaptable we are,” Burgess said. “We’re not the strongest, the sharpest, the most aggressive, but we adapt. We adapt in real time. And the prize always goes to the people that adapt fastest.”